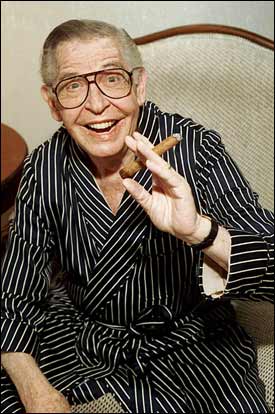

In the infancy of American television, one man stood taller than all others. Milton Berle, known to millions as “Uncle Miltie,” wasn’t just a comedian—he was a cultural phenomenon. In 1948, his Texaco Star Theater drew 80% of all TV viewers, an audience so massive that crime rates dropped, restaurants closed early, and families rushed home to catch his slapstick routines.

Berle’s face sold millions of television sets, transforming a new technology into the heart of American life. Yet when Berle died in 2002, his passing was barely a footnote—a forgotten relic in the industry he helped build.

How did a man who once defined American entertainment end up so alone, so overlooked, and so misunderstood? The answer is a cautionary tale about fame’s fleeting nature, the cost of relentless ambition, and the dark shadows cast by stage mothers and show business itself.

A Childhood Stolen for Fame

Milton Berle’s story began in Brooklyn, New York, in 1908, but his fate was sealed by his mother, Sarah Berlinger. Known later as Sandra Berle, she was the archetypal stage mother—obsessed, controlling, and determined to live out her own frustrated ambitions through her son.

When Milton showed a gift for comedy, Sarah dropped everything: her husband, her other children, and her own identity. She became Milton’s manager, cheerleader, and relentless promoter, even changing her name to match his rising fame.

Sarah’s methods were extreme. She laughed loudly in audiences to boost Milton’s confidence, pushed him onto stages without permission, and risked arrest just to get him noticed.

The rest of the family faded into the background, leaving Milton to shoulder the weight of his mother’s dreams. He later joked that Sarah made Gypsy Rose Lee’s mother look like Mary Poppins—a dark admission that speaks volumes about the emotional toll of his upbringing.

By age five, Milton was already acting in silent films. His childhood was a blur of work, not play. He appeared in more than 50 films before his eighth birthday, sharing the screen with legends like Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. By his teens, he was supporting the entire family as his father’s health failed. The pressure was relentless, and the entertainment industry’s appetite for talented children often came at the cost of their happiness and well-being.

The Vaudeville World: Grown-Up Dangers for a Child Star

At just 12, Milton’s world grew even darker. He later admitted losing his virginity to a chorus girl—a shocking revelation that underscored how vaudeville was no place for children. Late nights, adult jokes, and risky situations were the norm, and even Sarah’s constant presence couldn’t shield Milton from the dangers of show business. That experience, he said, shaped his view of relationships for the rest of his life.

Sarah’s control extended beyond Milton’s career. She sabotaged his romantic relationships, breaking up any that lasted more than three dates. Milton’s attempts to prove he wasn’t a mama’s boy led to a lifetime of chasing women, but he never escaped the need for his mother’s approval.

Education was an afterthought. Milton attended the Professional Children’s School in New York, a place designed more for working child actors than for genuine learning. He grew up in a bubble of competition, applause, and fame—forever cut off from normal life.

The Joke Thief and the King of Vaudeville

Berle’s reputation as a joke thief became legendary. In vaudeville, jokes were currency, and Berle was infamous for “borrowing” material. Bob Hope quipped that he watched Berle’s show to see how his jokes were doing, and Berle himself made light of it on air. Rather than hurting his career, the nickname “thief of bad gags” only added to his fame.

By age 21, Berle was headlining New York’s biggest theaters, performing six shows a day and starring in the Ziegfeld Follies. He worked tirelessly, moving from vaudeville to film to Broadway, always driven by his mother’s ambition and his own need for validation.

Berle’s drag performances were groundbreaking. In the 1920s and 1930s, cross-dressing on stage was risky—sometimes even illegal. But Berle’s over-the-top Carmen Miranda act made him a sensation, landing him on the cover of Newsweek and helping to normalize drag comedy decades before it was widely accepted.

The Birth of Mr. Television

On June 8, 1948, NBC aired the first episode of Texaco Star Theater, and television changed forever. Berle’s slapstick humor, wild costumes, and infectious energy captivated a nation. His show mixed vaudeville acts, music, and live commercials, creating a format that would define TV variety for decades. Stores sold out of televisions every Wednesday as families rushed to buy sets after watching Berle on Tuesday nights—a phenomenon dubbed “the Berle effect.”

NBC wasn’t initially convinced. They rotated hosts, but Berle’s connection with viewers was unmatched. By September 1948, he was the permanent host, earning the nickname “Uncle Miltie” after a single on-air joke. Suddenly, Berle felt like family to millions. At the show’s peak, he commanded up to 80% of the viewing audience—an unimaginable feat today.

Berle’s influence extended beyond entertainment. His show broke racial barriers when he insisted that the Four Step Brothers, a black dance group, perform live despite Texaco’s objections. “If they don’t go on, I don’t go on,” Berle told the sponsor, helping open doors for black performers nationwide.

Fame’s High Price and the Slow Decline

Berle’s success brought unimaginable wealth. NBC signed him to a 30-year contract worth $200,000 a year—over $1.5 million in today’s money—whether he worked or not. But the golden years were short-lived. As TV spread to rural America, Berle’s fast-paced city humor fell flat. Shows like I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners captured the heartland with family-friendly warmth, and Berle’s ratings plummeted.

NBC scrambled to salvage their investment, putting Berle on any show they could—most notoriously, Jackpot Bowling. Overexposure and changing tastes led to the first case of TV burnout. Berle’s frantic attempts to win back fans only accelerated his decline.

His personal life was equally turbulent. Two disastrous marriages to showgirl Joyce Matthews ended in heartbreak and scandal, fueled by Sarah’s meddling. Berle’s affairs became legendary, but they were more about escaping his mother’s shadow than genuine connection. Even his long marriage to publicist Ruth Cosgrove was haunted by old demons.

The revelation of a secret son, Bob Williams, born to showgirl Junior Standish, added another layer of chaos. Berle kept the truth hidden for decades, and when it finally emerged, it only underscored the dysfunction at the heart of his private life.

The Final Curtain: Isolation and Forgotten Glory

Berle’s fall from grace was brutal. In 1979, his appearance on Saturday Night Live became infamous as the worst episode in the show’s history. His outdated, offensive jokes and desperate need for attention led to a staged standing ovation and a lifetime ban from SNL. The industry that once revered him now recoiled.

His adopted son, William, published a memoir in 1999 that painted Berle as a neglectful, vain father more interested in women and gambling than his own child. The emotional wounds ran deep, and Berle never spoke to William again.

Berle’s last years were marked by health struggles and fading fame. Diagnosed with colon cancer in 2001, he refused surgery, believing he had time. He died less than a year later, on March 27, 2002. His passing was overshadowed by the deaths of Dudley Moore and Billy Wilder the same day. The man who once ruled TV couldn’t even command his final headline alone.

His funeral was modest, attended by old friends and stars, but the silence from Hollywood spoke volumes. Fame doesn’t last. The spotlight moves on.

Milton Berle’s Legacy: A Warning From the Past

Milton Berle’s life is a tragedy wrapped in laughter. He helped build television, brought America together, and broke barriers. But the relentless drive for fame, fueled by a controlling mother and a ruthless industry, left him isolated and forgotten. His story is a warning: the applause fades, the spotlight shifts, and the cost of chasing fame can be devastating.

Berle himself said it best in his final years: he no longer cared about making others laugh. He just wanted to laugh for himself. In the end, the tragedy of Milton Berle is not just that he was forgotten, but that he spent his life searching for something applause could never give.